History

What is the Yuma Crossing National Heritage Area?

National Heritage Areas are places where historic, cultural and natural resources combine to form cohesive, nationally important landscapes. The story of water and its impact on the people and land is the key to understanding the history of Yuma. Sitting at the narrows of the Lower Colorado River, Yuma was known as “The Gateway to the Great Southwest” and is the oldest city established on the Colorado River. The Yuma Crossing National Heritage Area encompasses seven square miles along the Lower Colorado River in Yuma, Arizona. It includes the Yuma Crossing National Historic Landmark, the Yuma Territorial Prison and Colorado River State Historic Parks, and over 3 miles of contiguous riverfront parks, trails, and 400 acres of restored wetlands.

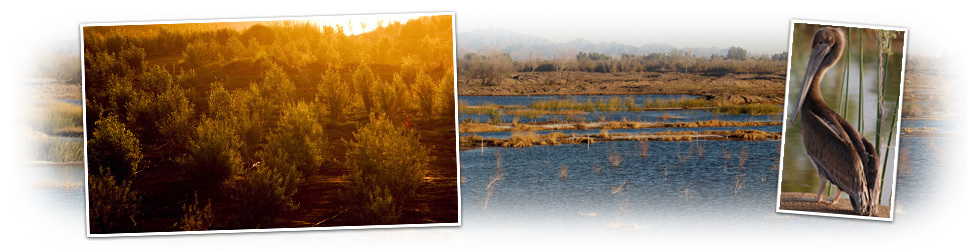

Miracle of Wetlands Restoration

Dams brought hydropower and a safe and secure source of water for the Southwest. However, controlled and decreasing levels of river flows meant that native cottonwood and willow forest did not regenerate and were replaced by dense monotypic salt cedar. This invasive non-vegetation cut the Yuma community off from the river, which spawned hobo camps and trash dumps. Many believed that high soil salinity and low river flows prevented wetlands restoration from ever returning.

Since 2001, a unique partnership of the Quechan Indian Tribe, City of Yuma, Arizona Game and Fish, Bureau of Reclamation, and Bureau of Land Management, managed by the Heritage Area, led to the restoration of nearly 400 acres of wetlands. Nearly 200,000 trees and native grasses have been planted. The Quechan Tribe built and opened the beautiful Sunrise Point Park below the Mission. The Heritage Area created a 3 mile hiking trail featuring a spectacular overlook. Fishing, birding and kayaking are but many of the ways that Yumans and visitors alike enjoy the wetlands.

America's Nile

If you eat a salad in the United States during the winter months, the iceberg lettuce you eat probably will have been grown in Yuma, Arizona. Yuma provides 95% of the winter fresh vegetables for the entire country, generating $2.5 billion annually of GDP for Yuma's economy and 20% of its jobs.

Yuma farmers produce more than 40 different kinds of vegetables and melons on more than 90,000 acres of land.

How did this phenomenon happen in the middle of desert?

It was part of President Theodore Roosevelt's vision to grow the Southwest and make the desert bloom.

With the assistance of the Bureau of Reclamation, Yuma's Irrigation Districts pioneered an intricate system of dams and canals, creating one of the most productive agricultural areas in the nation.

Laser leveling of farmland, efficient flood irrigation, and innovative conservation practices have made Yuma farmers leaders in the efficient use of Colorado River water. With the ever growing demand for water in the Southwest and limited supplies, the Yuma community is fully committed to working together to make sure that Yuma's agriculture remains sustainable for the long term.

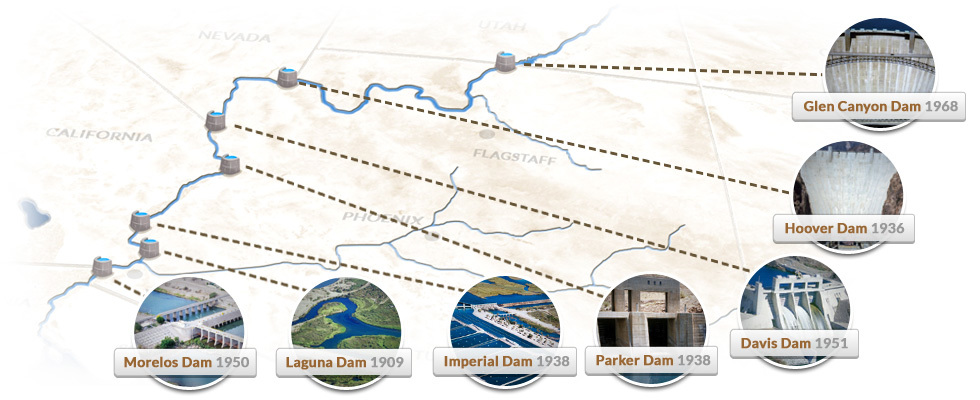

History of the Dams

American Nile - Taming the Colorado River for agricultural use and growth

During the 20th century, the Bureau of Reclamation undertook a herculean effort to assure a stable and secure source of water in the Southwest while generating "green" hydropower. While Laguna Dam near Yuma was the first dam and canal 1951 effort in 1909, the Hoover Dam, built in 1935, was an epic achievement. 726 feet high and weighing 6.6 million tons, it generates 4.2 billion kilowatt-hours of energy per year and greatly reduced the threat of flooding. Imperial Dam (1938) irrigates 600,000 acres of rich farmland and makes possible the growing of winter fresh vegetables for the entire nation.

Parker Dam (1938) provides water and power to Los Angeles, San Diego, Phoenix, and Tucson. Morelos Dam (1950) and Davis Dam (1951) together assures the coordinated delivery of water to Mexico to meet treaty obligations as well as generating nearly 1 billion kilowatt-hours fo net energy per year for Arizona, Nevada, and California. Glen Canyon Dam (1968) was the last dam built on the Colorado River, creating storage capacity of 27 million acre feet of water, more than all other dams combined. This system of dams effectively made possible the growth of the Southwest and a vibrant agricultural sector in the desert.

The Challenge of Unintended Consequences and A Return to Balance

The Challenge of Unintended Consequences and A Return to Balance

Yuma leads the way in fostering a return to balance on the Colorado River.

The positive impacts of the dam system were immediately obvious, but the unintended consequences of such a tightly controlled river only became apparent over time. The effective end of any flooding meant the loss of natural regeneration of native forests.

Once home to 400,000 acres of cottonwood and willow forests, the Colorado River, particularly the Lower Colorado River, suffered degradation of its eco-systems with severely restricted flows and invasive vegetation. Yuma suffered significantly as the dense non-native vegetation virtually cut the community off from the river.

The 1,400 acre Yuma East Wetlands (YEW) was one of the most ecologically altered riparian and wetland landscapes of the Southwest due to nearly a century of flow regulation, channelization, high soil salinity, non-native species invasion, deforestation and wildfires. However, a unique partnership of the Quechan Indian Tribe, City of Yuma, farmers, and state and federal agencies came together to restore 400 acres, planting nearly 200,00 native trees and grasses. What was considered "impossible" 20 years ago has become a reality. Today, in partnership with the Bureau of Reclamation's Multi-Species Conservation Program (MSCP), the East Wetlands is sustainable with 50 years of maintenance funding.

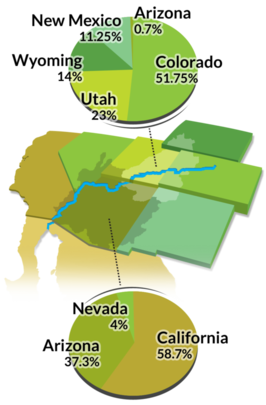

River allocation - resulting shortage we have today

The Colorado River Compact is a 1922 agreement among seven U.S. states in the watershed of the Colorado River governing the allocation of the water rights to the river's water among the parties. The agreement allocated the water equally between the Upper Basin states and Lower Basin state with each getting 7.5 million acre feet. Mexico was also granted 1.5 million acre feet. Since then, a series of agreements, compacts, and settlements have resolved the often contentious relation among the states in what is called "The Law of the River".

However, the amount of water allocated was based on an expectation that the river's average flow was 16,400,000 acre feet per year.

Upper Basin

7.5 million acre·ft/year

Lower Basin

7.5 million acre·ft/year

Apparently, when the compact was negotiated, the period used as the basis for "average" flow of the river (1905-1922) included periods of abnormally high rainfall. Subsequent studies, however, have concluded that the long-term average water flow of the Colorado is significantly less.

Estimates range from 13,200,000 acre feet to 14,300,000 acre feet per year. The return of drought conditions and ever growing demand from continuing growth in the Southwest have forced the states to agree to methods to manage and share in the coming shortages.

Future of the river

What our nation must do moving forward

Those of us who depend on the Colorado River for their lives and livelihood face a serious challenge. A recent Bureau of Reclamation study detailed that over the next 50 years, increasing demand for water will exceed diminishing supplies.

If water users fight over the shrinking supply, everyone will lose. Instead, the focus needs to be seeking innovation in conservation and water enhancement. To do so, the effort must emphasize collaboration and building partnerships among diverse stakeholders.

The Yuma Crossing National Heritage Area has developed plans to tell the story of the past, present and future of the river at the current Colorado River State Historic Park.

The plan features the construction of The Center for the Future of the Colorado River, intended to raise the awareness of the general public ( as well as policy-makers) of the challenges facing the Colorado River-- explaining the history of "how we got here" and the many legitimate needs which compete for this scarce resource. More importantly, it is intended to open a dialogue among all users of the Colorado River on how - together - we can overcome these considerable challenges through conservation, more efficient use of water and water augmentation.